First a few words in place of a glossary for non-archaeologists. The stone age, like Ceaser's Gaul, is divided into three parts: Palaeolithic, Mesolithic, and Neolithic with further subdivisions. Lithic simply means stone, and Palaeo, Meso, and Neo mean respectively 'old' (from Greek palaios), 'middle' (from Greek misos) and 'new' (from Greek neos).

The Palaeolithic period is an unimaginably vast length of time stretching back from the end of the last Ice Age to the dawn of tool-making humans (Homo Habilis) some 2.5 to 2 million years ago, a period covering 99% of our existence.

The Mesolithic began with the Holocene warm period around 11660 BC as the last glacial period ended. Mesolithic societies were the hunter-gatherer communities that inhabited Europe in the millennia between the Last Ice Age and the dawn of agriculture, spanning some 5,000 years between 12,000 and 7,000 years ago. Much happened during this period, the melting ice caused catastrophic tsunamis from the rising seas detaching Britain from the continent around 8500 BC. Woolly rhino, mammoth, and giant deer became extinct, whilst reindeer and elk herds moved north. In the warmer clime they were replaced by red deer, roe deer, wild pig, aurochs, and smaller herds of elk. In eastern Denmark auroch and elk became extinct by the later Mesolithic.

Warfare was endemic, 44% of the late Mesolithic burials in Denmark display evidence of traumatic injuries on their skulls consistent with having being struck by axes, in Sweden and France it was comparatively lower at 20%.

Alongside these bludgeoning injuries there is also widespread evidence of arrow wounds. ... A rather different insight into violence comes from Ofnet in Bavaria where, in 1908, two close-packed clusters of skulls were found in pits: there were six in one group and thirty-one in the other. Men, women and children were represented: most of them had been bludgeoned to death before having their heads severed. This incident took place some time around 6400 BC. (Europe Between the Oceans 9000 BC -AD 1100, Barry Cunliffe, pp 84-85).See also Origins of war: Mesolithic conflict in Europe and Violent Stone Age hunters.

The Neolithic is characterized by the use of ground or polished stone implements and weapons; it marks the introduction of farming and the domestication of cattle, pigs, goats, and sheep. What is known as the Neolithic package consists of farming, herding, polished flint axes, timber longhouses and pottery. It began circa 8500 BC in the Near East in an area known as the Fertile Crescent, at the head of the rivers Tigris and Euphrates, in modern Iraq. It spread west, reaching Greece and the Balkans by way of Anatolia (Turkey) by 7000 BC then central and west Europe by 5500-5000 BC and finally in north-west Europe from well before 4000 BC. Radiocarbon dating shows that the first farmers were in Britain by 4400 BC, and Northern Ireland by 4000 BC. It was a time of great forest clearing and in the later Neolithic of megalithic stone circles, some 900 in Britain, of which the best known is Stonehenge built circa 2500 BC but first laid out around 3000 BC. The period lasted till around 3000 BC in south-east Europe, and about 2500 BC elsewhere. Regarding flint axes, if they are polished then almost certainly they are Neolithic. This seems to have started as a practical measure as in tree felling, wood clearance for agriculture, a polished flint is less likely to shatter than an unpolished one. But then polishing spread to the entire surface for aesthetic reasons making axes suitable as gifts or as means of exchange or as offerings to placate the gods.

The Danish Neolithic period spanned from 3900 to circa 1700 BC. The Mesolithic hunting people in Denmark had long had contact with the Neolithic societies of central Europe, but only around 3900 BC did the hunter-gatherers begin to cultivate the land and keep animals. Extensive wooded areas were gradually cleared, burnt and replaced with fields of arable crops and cattle, pigs and sheep appeared as domesticated animals. The big change was that groups became more sedentary as they could produce their own food, although the farming population continued for a long time to hunt and fish from the old settlements on the Danish coast.

The Chalcolithic Age ('copper and stone' from the Greek Chalcos copper), is the later Neolithic and Copper Age, from 4500 to 2500 BC.

Around 3600 BC, came the discovery that copper could be made harder by melting it with a small amount of tin, forming the alloy bronze. This may have been accidental. The earliest use of bronze was by the Egyptians and the Sumerians and was in use in south-east Europe originating in the Middle Volga region around the same time.

Although bronze was used from about 2500 BC, "The earliest appearance of a regular bronze-using economy is to be found in Britain and Ireland in the period 2200-2000 BC, after which it spread eastward and southward through Europe, reaching all parts by 1400-1300 BC" (Europe Between the Oceans 9000 BC - AD 1000, Barry Cunliffe, 2008, page 181).

None of these ages succeeded overnight, change was very gradual and Mesolithic societies lived alongside Neolithic societies for many centuries, for example the Mesolithic Ertebølle culture (hunter gatherers) adjacent to Danish Neolithic societies (herders and farmers). The spread across Europe of the Neolithic, from the Aegean to the British isles, took about 2,600 years (7000-4400 BC).

In warmer climates these stone age periods started and ended much sooner. For example, in the Middle East the terms differ as do the periods:

Upper Palaeolithic circa 43,000-18,0000 BC

Epipalaeolithic circa 18,000-8500 BC

Neolithic circa 8500-4500 BC

Chalcolithic (copper-stone) 4500-3300 BC

Early Bronze Age 3600-2000 BC subdivided into:

Early Bronze I 3600-3100 BC Sumerian culture develops.

Early Bronze II 3100-2700 BC Floruit of Sumerian culture - Egyptian early Dynastic Period.

Early Bronze III 2700-2300 BC Flourishing city-states - Egyptian Old Kingdom Dynasties 3-5.

Early Bronze IV 2300-2000 BC Decline/abandonment of city states.

Middle Bronze Age circa 2000-1500 BC:

Middle Bronze I-II 2000-1650BC Invention of alphabet - revival of urbanism.

Middle Bronze III 1650-1550 BC - Second intermediate Hyksos period.

Late Bronze Age Circa 1550-1200 BC

Metallurgy came late to the British Isles. For Britain it used to be defined as:

Early Bronze Age 2300 - 1400 BC

Middle Bronze Age 1400 - 1000 BC

Late Bronze Age 1000 - 700 BC

You will still see those sub-divisions, but recently the British Bronze Age has been redefined as:

Earlier Bronze Age (EBA) c.2300 - 1200 BCE

Later Bronze Age (LBA) c.1200 - 800 BCE

A final word, in archaeology culture means the beliefs and the way of life of a society whilst industry means the tools, which includes weapons, produced by a culture.

Flint and bronze axes, or 'celts' (pronounced 'selt', not 'kelt') have nothing to do with the much later ancient Celtic tribes. They are stone age implements made several thousand years before the Celts appeared and the Celtic religion evolved. Celt is derived from the (reputed) Latin celtis, 'stone-chisel, sculptor's chisel'. Human memory of them and what they were was completely lost by around 800 BC; they were frequently found and commented on but until the 18th century they were thought to be divine thunder bolts by all, a belief which persisted in the countryside until the 19th century. Water in which celts had been boiled was held to be a cure for rheumatism. But even in later Neolithic times they had become objects of veneration, the weapons of the ancestors, to be buried with the dead or offered to the gods. Later their common use was forgotten but they were retained in religious ceremonies. Herodotus (Histories 2.86.4) records that a flint knife, which he describes as 'a sharp Ethiopian stone', was used by Egyptian embalmers to cut open a body for mummification. Solemn treaties among Romans were ratified by the Fetialis sacrificing a pig with a flint implement and into historical times a flint was used in the Jewish rite of circumcision. All were rites which had been handed down from generation to generation from time immemorial, and in which the minute and careful repetition of ancient observances was the essential religious element. In like manner, when the use of bronze weapons and tools was but a faint memory, Sabine priests cut their hair with bronze knives and the Chief Priest of Jupiter in Rome used bronze shears for the same purpose.

1. Palaeolithic Acheulean hand-axe

The most successful tool in continuous use in human history, persisted unchanged for over a million years to about 100,000 years ago. Provenance southern Britain.

Length: 133mm, max width: 80mm, weight: 425gm (15 ozs). More photos and details of my Acehulean hand-axe here.

2. Danish Mesolithic, Kongemose industry core-axe.

The Mesolithic period in Denmark is dated from 12,500 until circa 3900 BC. The ice that covered the whole of northern Europe slowly retreated and the tundra moved into the dry landscape. Reindeer followed and so did the hunters. As the climate and landscape gradually changed over the following 10,000 years the land was populated by small groups of hunter-gatherers.

The Kongemose culture (Kongemosekulturen), named after a location in western Zeeland, was a Mesolithic hunter-gatherer culture located in southern Scandinavia ca. 6300–5200 BC. To the north it bordered on the Scandinavian Nøstvet and Lihult cultures. It was followed by the Ertebølle culture (about 5200–4000 BC).

Kongemose industry finds are characterised by long flintstone flakes which were used for making the characteristic rhombic arrowheads, scrapers, drills, awls, and toothed blades. Tiny microliths fixed into the edges of bone daggers were often decorated with geometric patterns. The main economy was based on hunting red deer, roe deer, and wild boar, supplemented by fishing at the coastal settlements.

Length: 188 mm, max width: 73 mm tapering to 31 mm at butt end, max thickness 43 mm, weight: 600 gm (1.3 lbs)

3. A 'bout-coupé' cordate bifacial knapped hand-axe

This is a fine specimen stylish and intensively worked, only the butt is a non-cutting edge. Found in the 2.7 Km tract between the villages of Montry and Coupvray, Seine-et-Marne, Île-de-France, about 35 Km east of Paris. This is an attractive honey-coloured Grand Pressigny flint which was much praised and exported widely in the third millennium, a prestige flint often found in elite burial assemblies.

Possibly Neolithic, from the Chasséen culture (circa 4500-3500 BC). However, this finely worked piece might be very much older: from the Upper Palaeolithic Solutrean Culture (circa 19,000-15,000 BC). Solutrean tools are relatively finely worked, bifacial points made with lithic reduction percussion and pressure flaking rather than cruder flintknapping. These techniques were not seen before the Solutrean and were not rediscovered for thousands of years after, skipping the entire Mesolithic period.

Length: 180 mm, width: 87 mm max tapering to 42 mm, 32 mm thick at centre, weight: 535 gm (1.18 lbs), a large hand-axe still razor sharp.

4. Seven Tenerian culture arrowheads.

Tenerian is the name given to a culture originating in the 5th millennium BC and lasting until the mid-3rd millennium in the then fertile area which became the Sahara Desert. This spans a wet period of Saharan history known as the Neolithic Subpluvial.

In the heart of what is now the Ténéré desert, one of the Sahara’s most desolate regions, new lakes and rivers fed lush vegetation that drew animal life and eventually people. The Ténéré remained verdant for most of the early- to mid-Holocene (10,000 to 5,000 years ago). The Tenerians were cattle-herders, fishermen, and hunters. Their graves show that they were a spiritual people, being buried with artifacts such as jewelry made of hippo tusks and clay pots. Circa 2500 BC the region became arid desert again, and the Tenerians vanished, possibly following the animals elsewhere.

5.

Nordic Early Neolithic thin-butted axe, circa 4000-3500 BC.

Nordic Early Neolithic thin-butted axe, circa 4000-3500 BC.

Length 133 mm, width 162 mm, tapering to 51 mm, maximum thickness 31 mm, weight 372 gm (13.1 ounces). Grey mottled flint.

Thin-butted (tyndnakket) axes are characterised by a more-or-less trapezoid outline, narrow towards the butt. The longitudinal section with the greatest thickness is towards the cutting edge and the normal cross-section is convex on the two principal faces and straight on the edges.

For an in depth guide to Danish thin butted axes click here.

6.

Nordic Early Neolithic thin-butted axe, circa 4000-3500 BC. Trapezoid outline, asymmetrical cutting edge. Grey flint, flaked and polished on both faces. Provenance: Denmark, ex Lord McAlpine collection No.262 A4.52(13). A photograph of this axe appears on page 62 of Antiquities From Europe and the Near East in the Collection of Lord McAlpine of West Green, published by the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford. This was the first axe I acquired, I bought it in York in 1994 for £160.

Nordic Early Neolithic thin-butted axe, circa 4000-3500 BC. Trapezoid outline, asymmetrical cutting edge. Grey flint, flaked and polished on both faces. Provenance: Denmark, ex Lord McAlpine collection No.262 A4.52(13). A photograph of this axe appears on page 62 of Antiquities From Europe and the Near East in the Collection of Lord McAlpine of West Green, published by the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford. This was the first axe I acquired, I bought it in York in 1994 for £160.

Length 147 mm, width 26 mm, weight 328 gm (11.6 ounces)

7.

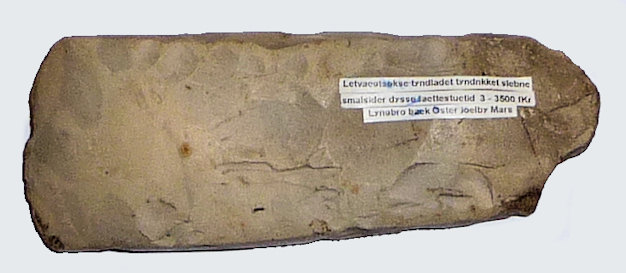

Neolithic polished flint thin-butted axe, dolmens/passage grave culture circa 3500-3100 BC.

Found in a field east of the village of Vester Jølby, near Dragstrup Vig, Denmark.

Neolithic polished flint thin-butted axe, dolmens/passage grave culture circa 3500-3100 BC.

Found in a field east of the village of Vester Jølby, near Dragstrup Vig, Denmark.

Length 150 mm, width 56 mm tapering to 47 mm, 21 mm thick.

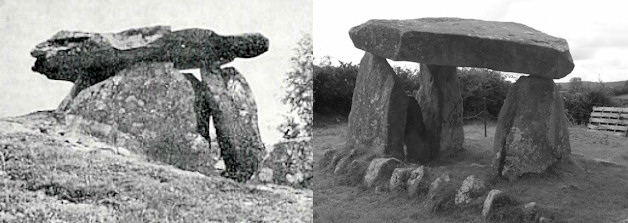

Dolmen at Haga, Bohuslaen, Sweden and Passage Dolmen at Ballykeel, Northern Ireland.

Dolmens were built of large granite blocks. The oldest dolmen chambers (3500-3200 BC) are small and thought to have been for single burials. The passage graves (3200-3100 BC) are larger than the dolmens and have space for many burials.

8. Neolithic highly polished hand-axe

A shaman's sacrificial axe? Circa 4000 BC, southern England, possibly imported high quality flint. There is evidence to suggest that Neolithic societies believed that polished flint celts possessed magical qualities. Such prized axes are often found in burials or in streams and rivers. Just as many still do now, people believed that behind the visible world was “another world” populated by invisible forces and spirits. These spirits of dead animals and humans had great power, and could be influenced by shamans.

Length 119 mm, width 60 mm, max thickness 34 mm; curved to serrated cutting edges on both sides. A veritable Neolithic Swiss-army knife!

9. Danish Late Neolithic thin-bladed thin-butted axe

In general these thin-bladed (tyndbladet) types are characterised by smaller size and a more slender cross-section combined in some instances with an expanded cutting edge although there are many variants. Their smaller size suggests their use in woodworking rather than primarily forrest clearance. These types may well have persisted into the Bronze Age.

Length 132 mm, width 48 mm tapering to 37 mm, thickness 13 mm tapering to 5 mm at butt end, butt width 36 mm.

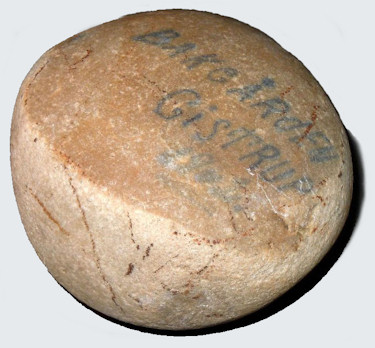

10. Neolithic hammerstone found in a back garden in Gistrup, Denmark, discoid shape. The side faces, gripped in the hand, were probably initially simply roughed out but became polished by decades if not centuries of use. Such hammerstones were used throughout the Mesolithic and Neolithic periods, 11600 to 1700 BC. Modern flint knappers have worked out that they were skilfully used as hard hammers to detach flakes from central flint cores in preparation for finishing with a soft hammer such as stag horn.

Max diameter 115 mm, min diameter 110 mm, thickness 70 mm, weight 1.45 Kg.

11. Mesolithic flake knife from a core block

Circa 5300 BC, Ertebølle culture. The long curved edge of this flake is razor sharp.

Length: 59 mm, average width: 40mm.

12.

Broken segment (arrowhead, spear point, knife?) mesolithic 47 mm, found by me in Shepperton, Middlesex, England.

Broken segment (arrowhead, spear point, knife?) mesolithic 47 mm, found by me in Shepperton, Middlesex, England.

13.

Danish Neolithic polished axe, possibly the reground portion of a longer one, the cutting edge has a lighter patina than the body.

Danish Neolithic polished axe, possibly the reground portion of a longer one, the cutting edge has a lighter patina than the body.

Length 99 mm, width 54 mm tapering to 40 mm at butt. Max thickness centre 24 mm curving to 14 mm at sides and to 8 mm at butt end.

14.

Danish Neolithic spearhead, very skilfully worked. Circa 3850 BC.

Danish Neolithic spearhead, very skilfully worked. Circa 3850 BC.

Length 85 mm, max width 21 mm, max thickness 8 mm.

15.

A Neolithic thin-bladed thick-butted (Younger) axe/adze showing highly skilled workmanship. Circa 3500-3000 BC. Provenance, Denmark. For a full description of this type see No. 9 above.

A Neolithic thin-bladed thick-butted (Younger) axe/adze showing highly skilled workmanship. Circa 3500-3000 BC. Provenance, Denmark. For a full description of this type see No. 9 above.

Length 134 mm, width 42 mm tapering to 25 mm.

16. Danish Late Neolithic/Bronze Age thick-butted axe/adze

"Dagger Period" industry 2500-2000 BC. This is contemporary with the Early Bronze Age in central Germany.

Between the years 2400 and 1500 BC, while the rest of Europe was well into the Bronze Age, Scandinavia lagged behind because it lacked copper and tin, the ores for bronze. Copper and bronze artifacts were traded into this region from the south, and flint remained the prime material for making tools for several more centuries, still skilfully knapped but no longer polished.

Length 136 mm, width at flared cutting edge 55 mm tapering to 28 mm at the butt; max thickness 25 mm. Butt symmetrical rectangle 28×21 cm.

Although this is a late example, thick-butted (tyknakket) types are typical of the Middle Neolithic period (circa 3500-2500 BC) and share the general characteristics of the thin-butted type with the exception of the butt itself. In the classic form this is square in section, although there are many variations.

See After the Ice: A Global History 20,000-5000 BC by Steven Mithen, page 526, note 20: "Three different types of flint axes have been found on the island of Zealand, each within a discrete area of the island; those in the southeast have a flared cutting edge, while those in the northeast have almost symmetrical sides."

17. Chinese Hongshan culture green jade votive axe, 5th millennium BC

The Chinese Neolithic began thousands of years before the European Neolithic, dating from around 12000/10000 BC at a time when the European Mesolithic was just beginning.

The Hongshan culture (circa 4700 BC to 2900 BC) was discovered in northeastern China in 1908. Hongshan burial artifacts include some of the earliest known examples of jade working.

Jade axes were held in the highest esteem in the West as well as the East. Two factors account for this: the rarity of the material and its extreme hardness making it very difficult to shape and polish in an age without metal. Two rare minerals are called jade: jadeite and the slightly less rare and less hard nephrite. Jadeite is 6.5 to 7 and nephrite 5.5 to 6 on the Mohs scale of hardness. To give some idea of how hard jade is (whether jadeite or nephrite), and for comparison, steel is 4 to 4.5 on the Mhos scale and window glass 5.5. Shaping and polishing a jade axe would have taken many months if not years. Evidently they were items of the very greatest prestige. Jade comes in a variety of colours of which green was the most sought after. A few Jade axes have been found in Britain, possibly made in northern France, from north Italian jadeite. In 1987 a polished jade axe-head dating from the early Neolithic, found at Newton Peverill in the Stour Valley, was purchased by Dorset County Museum for £24,000 with grants from the National Heritage Memorial Fund (£14,000) and the Victoria & Albert Museum Purchase Grant Fund (£8,000) to prevent it leaving the country.

This axe has had its cutting edge deliberately blunted with a polished 2 mm strip which suggests that it was not meant for use other than as a votive axe.

Length: 132 mm; max width: 60 mm, 28 mm at butt; weight: 227 gm (8.0 oz), material: green jadeite.

18. Mesolithic “spoon” scraper circa 5500 BC.

Length: 75 mm; max width: 57 mm.

19. Four British Neolithic arrowheads

Neolithic arrowhead (?) or possibly a tool for working leather; exquisitely carved with tiny serrated edges, workmanship seems too refined for it to be used as an arrow. Enlarged above to show fine detail. Provenance southern England.

Length 32 mm, max width 10 mm, max thickness 4 mm.

21. Three Mesolithic borers - Ertebølle culture (about 5200–4000 BC)

These, also called 'piercers' by some authorities, seem to have been tools for working bone, wood, and leather. The two smaller ones on the right have sharp cutting edges as well as a drilling bit whilst the larger one has a well shaped pommel for fitting in the hand for better leverage.

21a. This is a Danish Mesolithic antler dagger or halberd point, made circa 7000-5500 BC. It is 164 mm long, still needle sharp. Note the hole bored at the base, possibly made to mount it on a spear shaft. This is a rare item as very little organic matter survives intact from such a remote period.

22. Neolithic microlith blade

Several of these razor sharp flints were set in wood or bone and used as sickles or set as barbed spears and harpoons.

Battle-axe found at Corby Pike, Northumberland, England. The Battle-axe culture arrived in Britain in the late Bronze Age, around 1500 BC.

Length: 119 mm, max width: 50 mm, height: 50 mm, shaft hole diameter 22 mm tapering to 21 mm, weight: 500gm (1.10 lbs).

Late Neolithic battle-axe grave offering. Corded Ware Single Grave culture, a Glob subtype 'A' battle-axe found in Denmark. Made in a green hard stone around 2400 BC.

Length: 127 mm, max width at shaft hole:55 mm, shaft hole diameter 22 mm, weight 504 gm (1.11 lbs).

North-European battle or cult axe from the Single Grave culture (also known as the Corded Ware culture or Battle-axe culture) circa 2900-2000 BC. This period follows after the Funnelbeaker culture, known also as TRB (from German Trichterrandbecherkultur) ca 4000–2700 BC) and covered the area from the lands of the West Rhine to the east of the Volga. These axes were probably used for ceremonial purposes and for burial with elite males.

What fascinates me about these battle-axes is the endless patience that must have been exercised in boring the shaft holes millennia before metal was discovered, perhaps taking many many months of relentless work. From unfinished Swiss examples it seems that a hollow animal bone was used with sand and water to drill out a central cylinder, taking a day or more to progress less than a millimeter, or as John Evans put it after an experiment which he conducted in the 19th century So slow was the process, that two hours of constant drilling added, on average, not more than the thickness of an ordinary lead-pencil line to the depth of the hole. They must have been items of very great prestige.

Length: 149 mm, shaft hole diameter: 20 mm. Light to dark grey with rust-like patches, possibly diabase, an igneous rock.

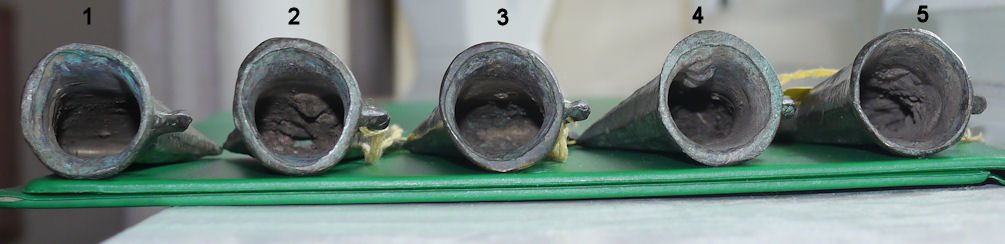

Axe No. 1 blade width 45 mm, length 96 mm, weight 105 gm.

Axe No. 2 blade width 46 mm, length 97 mm, weight 110 gm.

Axe No. 3 blade width 47 mm, length 99 mm, weight 148 gm.

Axe No. 4 blade width 47 mm, length 96 mm, weight 149 gm.

Axe No. 5 blade width 45 mm, length 95 mm, weight 100 gm.

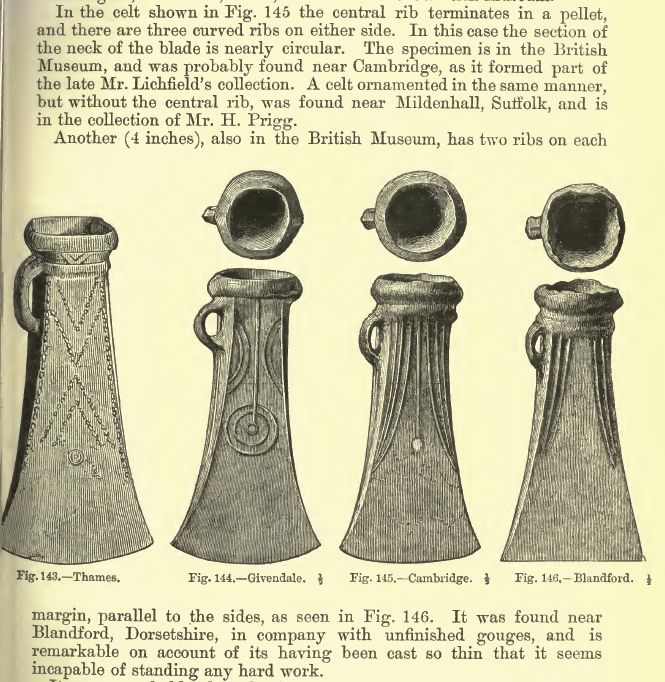

British socketed axes date from circa 1000 BC to circa 800 BC. These five celts are from a hoard of at least twenty found in the 1970s in a field near Berry Mound, the site of an Iron Age hillfort in the West Midlands of England. They are similar in form to axe No. 11.33, (Blandford type, LBA III, circa 800 BC) catalogued at page 105 of Antiquities From Europe and the Near East in the Collection of Lord McAlpine of West Green. Copper alloy: this type has a high tin content, averaging 20%, cast in such a way as to produce a tin-rich silvery surface. Such high tint content renders the bronze shiny but brittle. Thus the hoard was probably a sacrificial gift to the gods, and not intended for use. They are similar to one illustrated (fig. 145) at page 127 of The Ancient Bronze Implements, Weapons, and Ornaments of Great Britain and Ireland by John Evans (1881).

Bronze Age socketed axe found in southern England. This type, square section barrel with almost parallel sides and flared cutting edge, is typical for eastern England and is similar in form to axe No. 11.19, catalogued at page 105 of Antiquities From Europe and the Near East in the Collection of Lord McAlpine of West Green, published by the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.

Copper alloy: tin content for the type is around 7% to 11%. Length: 105 mm (4.1 inches) Width below loop: 28 mm (1.1 inches) Blade: 40 mm (1.6 inches). Weight: 200 gm (7 ounces).

Length: 145 mm (5.7 inches); blade width: 101 mm (4.0 inches); thickness of blade near socket: 19 mm (3⁄4 inch); socket width: 40 mm (1.6 inches); weight: 775 gm (1.7 lbs).

Roman glass, 1st/3rd century. Height 50 mm.

Peter Ghiringhelli B.A.(Hons), M.A.

2012

Home Page